Thursday, September 21, 2006

Monday, September 11, 2006

Festival de Valdivia: Part IV

Having gone to Bolivia the week before the festival and after having been immersed, at least for an instant, in the political process which is unfolding there, the Bolivian film Lo Mas Bonito y Mis Mejores Años (The Most Beautiful Things and My Best Years), became a natural draw for me. On the Lord Cochrane stage appeared this twenty five year old cochabambino named Martin Boulocq: long hair, Spanish features, dress jacket, jeans, and sneakers. While timidly presenting his film, he promises to come back at the end to answer questions.

The film begins. It takes place in Cochabamba, Bolivia, a city which became famous internationally a few years back when mass protests successfully thwarted the privatization of the public water supply. It is an urban landscape that has obviously suffered years of neglect. Immediately, we get the impression that this is some sort of a documentary. The dialogue, although almost inexistent, is very realistic, and the scene is filmed hap hazardously, coming in and out of focus with jolty frames, camera angles and distances that defy convention, the sound of the street outside is picked up as is a noticeable room tone. Someone works in a video rental place and for what seems like an eternity, nobody really says anything. Someone is trying to sell a car? You can't really tell. Slowly, we begin to situate ourselves in this gritty urban world and come to recognize our main characters. Before this happens, however, several people have already left the theatre.

Visually, it is definitely an acquired taste. Much more interesting is the way Boulocq approaches his film. Apparently, with no script (not one piece of paper) and with only a vague idea as to the structure of the story, the director places his cast and crew into a variety of concrete situations where improvisation is the rule. None of the actors knew what was supposed to take place and they were only supplied with concrete situations where they would have to improvise, not knowing what the other actor might do. It is somewhat similar to the way Sebastian Campos (Chilean director graduated from the Escuela de Cine in Santiago) directed La Sagrada Familia. The attempt was made to document a piece of "provoked reality". As such, the film can be considered a documentary as well as an instance of fiction. Excellent film editing by Guillermina Zabala.

The story is simple but very revealing. The quiet and bearded Berdo is looking for a way out of Cochabamba and in order to pay for his ticket, he has decided to sell his 65 Volkswagen, which eventually becomes the audience's main vehicle around the disturbed city. Victor, a video store clerk, becomes his best friend and helps him in the campaign to sell the car. Although they share a lot of time together, it is Victor who doses most of the talking and persuading, while Berdo, who is a very quiet and timid young man, passively absorbs his philosophical ranting. Victor is a troubled cochabambino, plagued with the impossibility of his projects and dreams. The only two things that are keeping Berdo from committing suicide, it seems, are Victor's "teachings" and the possibility of leaving cochabamba. The arrival of Victor's girlfriend Camila saves the story from floundering but also adds to the tormentuous relationship between Victor and Berdo.

The film is about how young people who are faced with a bleak reality and an even less appealing future struggle to maintain some level of dignity. It is a groundbreaking film which indirectly tackles some of the persistent social problems in Latin America.

Friday, September 08, 2006

Festival de Valdivia 2006: PART III

The Austral University students were tremendous Pink Floyd fans, singing and mumbling the words to typical Pink Floyd songs while strumming on their guitars in front of their porch; they seemed to be living in some fairy tale world, just relaxing and playing music in the shadow of their rustic cabin. We woke them up a little with our city enthusiasm and I played some annoying Radiohead for them. They seemed to appreciate it.

We re-entered the world of films soon after. It was late afternoon by the time I made it to the Austral campus, where two of the festival's screens were located (just on the other side of the Valdivia river), the documentary about the Mapuche had already started. The film, called We Pu Liwen (New Dawn) and directed by Francisco Toro Lessen, was your typical film about Mapuches and there was very little that could be rescued. The importance of mapuche culture, the struggle to maintain mapuche identity alive, etc.

This specific documentary focused on the Mapuche Cosmovision and included poetry by Lorenzo Aillapan. The problem with these documentaries is that the Mapuches depicted tend to automatically revert to a very rehearsed discourse about their identity and the struggle to keep it alive. At no point do we feel that we really understand the subjects better or that we are closer to them as a result of the exposition. Quite frankly, images of mapuches with their ponchos walking through the wilderness flanked by the sounds of the kultrun and the trutruca have become quite cliché and it's not clear whether they contribute anything new to the mapuche documentary genre. Sometimes it's important to expose the subject's own discourse and not just take it at face value.

The best of Sunday, we thought, would be reserved for the Chilean premiere of Almodovar's latest film, Volver (Return). This was clearly the public's favorite. Penelope Cruz was scheduled to present the film, but for some reason, she didn't show up and the supporting actress, Lola Duenas, presented the film instead. There were a lot of cameras hovering over the "almodovar girl" and the intense light they were constantly beaming on her while could only have been annoying. The Lord Cochrane theatre, where most of the competing films were screened, was overflowing with people and we could sense the intense hype surrounding the film.

Of course, a film with semejante level of hype can only become a let-down. Surprisingly, however, there are quite a few things that made Volver, Almodovar's latest festival winner, worth remembering. For one thing, Penelope Cruz. It is truly remarkable to watch and hear her move around the screen. She is in constant motion, both physically and emotionally. While in one minute her face explodes in laughter as she prances around an equally colorful interior, in another it reveals a precise level of panic and fear as she tries to cope with the complicated realization that her daughter has killed her husband.

All this, of course, complimented by fantastic dialogue which dominates each scene, it provides the essential energy for each character and never for a second feels forced. Completely spontaneous. And never do we doubt for a second that Penelope Cruz is Raimunda, never does it occur to us that she's an actress playing a part, until, of course, the spell is broken and the film comes to an end.

More so than in other films where he clearly accentuates his female characters and fills them up to the brim with an exaggerated sense of confidence, emotion, sex appeal, intelligence and physical and intellectual panache, Almodovar really goes the extra mile to pay homage to the female race. In many interviews given around the world, he has stressed that for him, this film is a return to his childhood, which he remembers to be predominantly marked by women. Indeed, it is made clearer with Volver that his fascination for the female character, translated cinematographically into a wonderful spectrum of female color, emotion and intelligence, is what drives his filmmaking.

In Volver, men simply don't exist; they are not important, they are secondary at best and often simply fill spaces that need filling, to reaffirm their own obsolescence or to consecrate their obvious dysfunction in the world. Men are there because they played some marginal partin the creation of their daughters (often in unconventional ways), but not because they contribute or because they deserve any real screen time. In the world of Volver, Raimunda (Penelope Cruz) is alone to construct her life and to raise her daughter in spite of her husband (who is, basically, a loser imported from a different world or genre altogether). When the husband is killed off early in the film, his sudden departure from the world of the living automatically becomes a problem of what to do with the body; his absence is never interpreted as a significant loss nor seen as a tragedy in its own right.

In Volver, women are masters of their own destiny. They are hardly well organized, disciplined, overly confident (like the corporate women in El Metodo) or even emotionally or economically stable for that matter, but that doesn't necessarily translate into a loss of will or control, or the sudden interruption of a life well-lived and felt. Raimunda is a mess, she works as a sub-contracted maintenance worker in an airport, has no other clear or stable source of income (but she does stumble upon an opportunity to take over a restaurant and she doesn't hesitate for a second), she is haunted by a mysterious fire which claimed the life of her mother (whom she has a lot of unfinished business with), her sister Sole runs an illegal beauty salon out of her messy apartment, she has a daughter who doesn't know where she came from, but this never for a moment brings into question Raimunda's freedom. She works it out, then panics, relaxes again, figures it out again, devises plans, carefully calculates her options, carries out her missions, explodes in sadness again, recovers again, and all of it done with unquestionable grace (she even takes a piss on screen, again, full of grace). But never for an instant is her will challenged, her grace compromised, never for one second does she stop feeling and living a su estilo; she is the master of her domain and is never required to explain anything or give up the essential elements of being human- those elements that are so sadly repressed in men (and exaggerated in women by Almodovar).

When we think about the women in Almodovar's world and then switch over to the women in Jafar Panahi's The Circle, we might as well be talking about two different species. The interesting thing about this, especially when we consider the awesome potential films have to convey such contrasting worlds, is that we're not talking about two different species.

Jafar Panahi is a critically acclaimed Iranian director whose films deal with the realities of modern life in Iran. This year, the Valdivia Film Festival has a retrospective which brings some of his most acclaimed films to the tail end of the world for the very first time.

On the last day of the festival (and here we are obviously jumping ahead in time), Panihi presented his film The Circle which deals with the harsh realities that Iranian women have to face in post-revolution Iran. Here, urban Iranian women are depicted as defeated souls, lost in a maze of indifference, in a Tehran which brutally ostracizes and marginalizes women ("you can't go anywhere without a man"). The film takes turns following three loosely related female characters through the streets of Tehran. The first two women have been granted temporary release from prison and have no intention of returning, while a third women, whose story is casually taken up by the film towards the end, has escaped outright from prison and is desperately seeking arrangements for an illegal abortion. They frantically try to achieve their objectives, the first two wish to flee to a far away place and the pregnant woman seeks the help of old friends, but they fail to gain ground in an extremely closed society. There are many alludes to the question of freedom in Iran as well as to male domination, consequently, the film was banned there.

Comparing the treatment of women in the two films, we see immediately that there is nothing beautiful or worthwhile about the Iranian women in The Circle other than their obvious courage. One gets the impression that most of the time invested went into portraying Tehran as this terrible place full of danger and indifference at every corner, while almost no attention was dedicated to actually developing the female parts, characters who will no doubt be seen by western audiences as representing Iranian women in general. For the most part, they come across as one-dimensional and shallow. One never really feels a sense of injustice because the women never reveal their true humanity in the film. It sometimes feels as if Panihi, by forgetting to give these women personalities, is just as guilty of repressing them as the society he is trying to critique.

Wednesday, September 06, 2006

Festival de Valdivia 2006 PART II

Our first day of film-going went off quite smoothly, beginning in Argentina with a hard look at how the print media can distort political events with significant ease, and finishing up in Spain with an excellent character-driven film which attempts to show whether decent human beings can emerge from a highly competitive and psychological corporate selection process. In all, our Saturday movie-going session lasted about nine hours and was full of interesting surprises including a wonderfully delightful Chilean film directed by Rodrigo Sepulveda with a wonderful performance by Chilean actor Jaime Vadell.

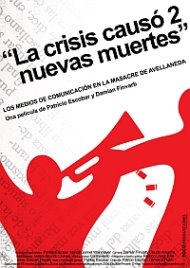

La Crisis Causo 2 Nuevas Muertes (The Crisis Caused Two New Deaths) was the June 27, 2002 Clarin newspaper headline which referred to the outcome of a violent barricade confrontation in Buenos Aires between Piqueteros and the police the day before. Two young activists, Maximiliano Kosteki and Dario Santillan, were murdered by the Argentinean police on that day but the newspaper Clarin, despite having possession of the incriminating photographs (and selectively publishing the ones that were ambiguous), distorted the events by claiming they did not have any information on who killed the piqueteros. The mainstream media followed Clarin's lead and distorted the events even further suggesting that a rival piquetero group was responsible. The film is a well- documented call for justice in the media, which is an important struggle in Latin American social movements. It is very common for the media in Latin America to play an active role in political confrontations, usually taking the side of law, order and stability and often blurring the repressive methods which are used to control popular opposition to neoliberal government policies. Very interesting. The film could have used a more concise "montaje" and a better narrative device; at times the information is overwhelming and the documentary tends to hit us over the head with its central thesis. A few technical flaws, especially in sound, but overall a great documentary and a good window into what has taken place recently on the other side of the Andes.

La Crisis Causo 2 Nuevas Muertes (The Crisis Caused Two New Deaths) was the June 27, 2002 Clarin newspaper headline which referred to the outcome of a violent barricade confrontation in Buenos Aires between Piqueteros and the police the day before. Two young activists, Maximiliano Kosteki and Dario Santillan, were murdered by the Argentinean police on that day but the newspaper Clarin, despite having possession of the incriminating photographs (and selectively publishing the ones that were ambiguous), distorted the events by claiming they did not have any information on who killed the piqueteros. The mainstream media followed Clarin's lead and distorted the events even further suggesting that a rival piquetero group was responsible. The film is a well- documented call for justice in the media, which is an important struggle in Latin American social movements. It is very common for the media in Latin America to play an active role in political confrontations, usually taking the side of law, order and stability and often blurring the repressive methods which are used to control popular opposition to neoliberal government policies. Very interesting. The film could have used a more concise "montaje" and a better narrative device; at times the information is overwhelming and the documentary tends to hit us over the head with its central thesis. A few technical flaws, especially in sound, but overall a great documentary and a good window into what has taken place recently on the other side of the Andes.The great thing about documentaries is that they take you places you've never been before even if you've been there before. This is the central idea of the Venezuelan documentary, Macadam, directed by Andres Agusti. This film shows us a harsh Venezuela through the eyes of a highway. In a car or on a bus, the highway is a vessel that takes you past a thousand stories and realities you will never see or hear. These stories, nevertheless, exist on the ground and on the side of a road where the fierce sound of cargo trucks and microbuses passing by at excessive speeds interrupts an otherwise tranquil landscape of human existence. This filmmaker brings us close to those whose faces we see blurred as we speed by indifferently on our way through. And so even though the highway which dissects a Latin American country is a place most of us have experienced, we nevertheless learn something new about the lives those faces represent. The lack of narration and the lack of momentum might bother some people, but I think the vehicle of the film, this sort of slow introduction to each of the characters and the obsessive attention to detail interrupted abruptly by a passing bus whose driver is blasting cumbia, reflects effectively this harsh contrast between the fast-moving economic highway (flanked by the ubiquitous oil pipeline) and the slow passage of time lived by real people on the ground.

The second half of the day was reserved for fiction. The Chilean film Padre Nuestro was a delightful surprise. It is the story of a dying man whose dying wish is to reunite his estranged family for one last group photo in Quinteros, a beach community in central Chile, but not before spending a night out on the town in Valparaiso with his younger son who helps him escape from the hospital where his prognostic is bleak. He is a man who has lost everything that is important to him, his wife and his three children, and although he doesn't regret anything he has done (to the disdain of his daughter, played by Amparo Noguera), he recognizes that the only thing that matters is his family, whom he loves despite his fatherly limitations.

The second half of the day was reserved for fiction. The Chilean film Padre Nuestro was a delightful surprise. It is the story of a dying man whose dying wish is to reunite his estranged family for one last group photo in Quinteros, a beach community in central Chile, but not before spending a night out on the town in Valparaiso with his younger son who helps him escape from the hospital where his prognostic is bleak. He is a man who has lost everything that is important to him, his wife and his three children, and although he doesn't regret anything he has done (to the disdain of his daughter, played by Amparo Noguera), he recognizes that the only thing that matters is his family, whom he loves despite his fatherly limitations. Our first day culminated with an exceptional film called El Metodo, a Spanish film directed by the Argentinian Marcelo Pineyro. This film takes us into the dark world of the corporate selection process. The story unfolds almost entirely in a corporate boardroom where a handful of candidates for the position are forced to participate in a highly evolved psychological selection game breaking all the rules of decency and mutual respect in the process. As a mass anti-globalization protest goes on below in the streets of Madrid, in the high rises we find out just how ruthless people can become in order to succeed in the highly competitive corporate world. The film's script is really incredible, as are all of the performances. Although we only share a few hours with the characters, the fluid and cutting edge dialogue is very entertaining and revealing.

Our first day culminated with an exceptional film called El Metodo, a Spanish film directed by the Argentinian Marcelo Pineyro. This film takes us into the dark world of the corporate selection process. The story unfolds almost entirely in a corporate boardroom where a handful of candidates for the position are forced to participate in a highly evolved psychological selection game breaking all the rules of decency and mutual respect in the process. As a mass anti-globalization protest goes on below in the streets of Madrid, in the high rises we find out just how ruthless people can become in order to succeed in the highly competitive corporate world. The film's script is really incredible, as are all of the performances. Although we only share a few hours with the characters, the fluid and cutting edge dialogue is very entertaining and revealing.

Tuesday, September 05, 2006

Festival de Valdivia 2006: PART I

The clasico Tur-Bus service is the crappiest spike in the Tur-Bus service trident. The other two are the "ejecutivo", which you can bet has not one single "ejecutivo" on it, and "cama", which is essentially a bus full of jerk-offs lying horizontally. "Clasico", by the way, is code for "there's no way my legs are fitting in there!" Since our bus was a night bus, complete with blankets contaminated with chicken pox and pillows designed for Lilliput, our bus careened out of the alameda bus terminal with a fifty-fifty chance of crashing head-on into something large and immobile.

The clasico Tur-Bus service is the crappiest spike in the Tur-Bus service trident. The other two are the "ejecutivo", which you can bet has not one single "ejecutivo" on it, and "cama", which is essentially a bus full of jerk-offs lying horizontally. "Clasico", by the way, is code for "there's no way my legs are fitting in there!" Since our bus was a night bus, complete with blankets contaminated with chicken pox and pillows designed for Lilliput, our bus careened out of the alameda bus terminal with a fifty-fifty chance of crashing head-on into something large and immobile.The "auxiliar" made his way down the aisle in typical neanderthal fashion, writing down passenger names for post-crash identification purposes, and I suddenly realized that I was hungry for bus food. Traveling around Latin America by bus will never be complete without bus food. It doesn't really matter what time of day it is, it is scientifically proven that buses in Latin America, even Chile, trigger immediate hunger. If for any reason you've been taking it easy on the cookies, chips and colored drinks, a night bus ride is your chance to catch up on lost moments of junk food sucking. Standard bus food consists of "Fracs", or local equivalent, a tube full of generic "pringles", a cheese-bread thing, and for dessert, Unimarc manjar balls with cocunut springles. Fantastic! The rest of the bus ride consisted of brief intervals of sleep and praying.

First Impressions of Valdivia

Arriving in Valdivia early Friday morning was, for me, somewhat of a let-down, at least visually. Except for the happy meeting of rivers, a few mediocre forts (that charge you for the view they afford!), and the overall country feel, Valdivia is just another "could be anywhere" town in southern Chile. Everybody had told me that Valdivia was "something really special", and I'm sure they know what they're talking about, and I'm sure they're right (I've only been here for one day, after all), however, I can't help but feel the way I do, "let-down". Maybe the "classic" Tur-Bus night service had something to do with it, or the food I ate which was making me physically nauseas, the point is Valdivia, at least at first glance, left a lot to be desired.

No Spanish

Ironically, part of the problem is that this end of Chile was never really conquered by the Spanish (people here speak valdivian) and so you see almost no Spanish architecture, which is so visually rewarding. There are no "fuck all" cathedrals with their pompous and exaggerated details, no sign of the visual wealth (at least) left behind in places like Potosi or Sucre in Bolivia. I'm a spoiled traveler, I guess, and maybe it's a good thing the Mapuches were never really overrun by the Spanish, except that a few years later they were overrun by the Chilean state in a "process" much more abrupt and bloody in comparison. With the Spanish, at least you had this sort of missionesque "we're here to save you from yourself and please cover your testicles" type of discourse with the "natives". With the Chilean army, it was a much more modern, and hence cold, type of "extraction" which encouraged post pacification immigration and turned these parts into boring towns full of drunk Germans. En fin.

Not Santiago

Most of the praise for Valdivia, I suspect, is exaggerated by Santiaguinos because for them, any place that is not Santiago seems like a paradise, especially if there are a few rivers you can stare at without feeling nausea or air for your lungs. The other thing that disappointed me was the porfiado presence of commercial franchises that also contribute to the homogeneity of southern Chile. It's like the municipality tries to "improve" the city by making it look more like Santiago, complete with its "fuck all" shopping malls, instead of more like Valdivia. So when you're in town, you see the same mediocre chains of decadent commercial interests (which people, in any case, go nuts for), malls, jumbo supermarkets, McDonalds, Mass Pharmacies, Cineplexes, Electrodomestic department stores, Blockbusters. I guess they call this "progress", "integration", "modernity" or the latest catch word, but in Sucre, or other places in Bolivia, for example, you don't really see those sorts of things and you would never suggest that the answer to all their problems, of which there are plenty, is to bring in a La Polar or a Blockbuster.

Swans with Black Necks

The other thing which has marked Valdivia lately has been its leading role in the so-called "environmental wars" that have been "waged" in Chile, recently. Of course, the Pulp treatment plants have been present in the south for many years and contamination is not a new thing; the environmental "issue", however, is a relatively new phenomenon. Last year, the media exploded the issue of the black neck swans, who basically all died, quite dramatically, and on TV. Residuals from a pulp mill killed off the swan's primary source of nutrients. The media went ape shit and government representatives were forced to make a few speeches about the importance of the environment and on the importance of not killing swans. The plant closed itself down (which was bizarre on the one hand and clearly evidence of some sort of secret deal reached with the government on the other) and then opened again with promises to contaminate the coastline instead. A few complicated and scientific-sounding studies were released to the media and the whole country became confused as to the real causes of the deaths of the swans. Was it the lack of food, or was it a mass swan suicide promoted by too much food?

En fin, in the end, nothing was done and it became clear that the environment, while extremely noble and important, cannot jeopardize the nobler pursuit of supplying Asian countries with lots of pulp from our unrenewable forests in exchange for cheap washing machines, televisions, sandwich makers, and consumer debt. Nobody, by the way, brought up the issue of human contamination. Those types of effects are considered "long term", which in Chile, as in most countries, is a concept that is rarely taken seriously.

Drunk Germans

There's also beer here in Valdivia! Kunstmann beer is a German beer made in Valdivia (about 10 km from the center of Valdivia) and in their merchandizing material you can make out the glorious X Chilean Volcano and the beautiful Lakes and all that. We were assured on the tour that the company is one hundred percent Chilean, providing jobs for as many as 32 Valdivians (!) and generously supporting the local economy and municipality (US$ 6,000 a year!). In the museum, along with the typical rudimentary machines used to grind stuff, you can also see the long string of bearded Germans who've owned the company over the years as well as an assortment of photographs taken during the Valdivian version of a beer fest (complete with the queen of rivers looking quite German). There's a substantial German influence in this region and, call me crazy, I get the impression that the people in the oversized supermarket stare at me with German eyes!

Film Festival

But the real reason our team of documentary film students from Santiago is here is to take part in the 13th International Film Festival of Valdivia! I have no idea how this festival began and why it began in Valdivia (must find out!) but it seems to be a big deal in Chile. The Chilean film industry is almost non-existent but what little there is seems to conjugate here at the end of August to enjoy and critique the latest Chilean features, shorts, and documentaries alongside student offerings, animation, and a few international films that are incorporated into the main competitions and also as part of a series of special "homages" and "tributes" and all that payasada. This year, there is a strong focus on Argentinian films. Included in the program is a historical and cultural forum lead by Luis Bocaz, analyzing the cultural impact these political films have had on Argentinian society. The majority of these films tackle the often violent political developments in Argentina during the second half of the twentieth century.

Aside from this cycle of political film analysis, there are a variety of films that interest me, or filmes que me tincan. There are documentaries that tackle interesting and complex social and economic realities, especially in Argentina, there is an attempt to define the Mapuche cosmovision, there is a much-awaited and unreleased Chilean comedy, there is the latest Almodovar film, and there's a groundbreaking Bolivian film! Topping the list of films that are in competition for best feature-length is the worst and most pretentious Chilean film in history, "Fuga", a film whose executive producer is also part of this year's jury for the same category. Hello? So far, our pre-festival experience has given us the impression that this event is as big of a let-down as Valdivia, and this "controversy" forms part of that first impression. It's just a first impression though.

Tuesday, August 22, 2006

Getting Closer: From Dunkin Donuts to Free Trade Zones

Shortly after landing in Iquique we realized that the best move would be to take one of the daily Bolivian buses heading late at night towards the border. Discarded were the ad hoc plans to spend the night eating and drinking merrily with my uncle Ronald Rauld who lives in Playa Brava at the southern end of the city. Catching up with my uncle and his wife Pepa was scrapped and replaced by a brief visit to the local supermarket to stock up on essentials (ie. Sahne Nuss Chocolate, crackers, nuts, wine, and chumbeque!) before our 9 pm departure into the Andes. But just a few hours before, back in Santiago, we had spent a couple of memorable moments at the Arturo Merino Benitez International airport just prior to departure. Thanks to the wonders of the neoliberal concessionary system of building large things that otherwise can't be built with money we don't understand, this particular airport facility, the same one that welcomed the entire APEC squad, is actually one of the most modern in all of south america and it is complete with its own internal Dunkin Donuts and Starbucks Coffee. To our surprise, our checking-in process lasted just a few short minutes, and so we were suddenly confronted with a giant monster of spare time which hung over us like a lemon tree, and which, in a certain sense, pressured us into spending it wisely and responsibly. We decided immediately, then, to bug the nice gift shop attendants who seemed busy enough not to appreciate it tremendously.

I was curious about the latest headline on the La Tercera front-page. At this point, the entire world was wondering what the fuck was wrong with Fidel Castro who had suddenly gone off the radar screen leaving the entire world fumbling with the question: "uh, what's wrong with Fidel Castro?" And other questions as well: "What the hell is 'Diverticulitis'? Well, La Tercera decided to run that headline and I thought it strange to include a word that only a doctor living in the Amazon might know after consulting his medical books which were back at home anyway, especially since the idea was to clarify Fidel's medical condition, not cloud it even further. In any case, we would later catch up with Fidel, or at least his legacy, in La Paz for his 80th birthday. It served as a foreshadowing type of moment in a novel that has yet to be written. So the nice attendants didn't have a clue but they did talk to me about their job and how far they had to travel just to work there, etc. We walked around in circles a few times, admiring the towering suitcase art, before heading in for our mediocre full-body inspection.

Once on the "inside", we were free to relax at the Dunkin Donuts. I had never seen such a high-tech and elaborately staged on-line cashier system, complete with debit card pin-punching thingy. I must say I was a little surprised when the woman gave me three receipts for my purchase, which was essentially two donuts, one with manjar and another with blue things on it. Very bizarre, but that didn't stop Tomas Dinges from building a strong relationship with the lady who had just completed my transaction. He started to have a philosophical conversation, no less, about donut dough and then went into sharing his crazy idea for donuts made from "sopaipilla" dough. I think in the end he succeeded in his mission to find a business partner for his elaborate sopaipilla donut empire. I insisted that a donut with sopaipilla dough just equals a sopaipilla, and if you start putting colorful and sweet things on a fried, salty, pumpkin-like mass of dough, people are bound to start throwing up. Perhaps on a street cart, where you can sell anything and people will eat it, but as a business idea I though it was a stretch.

Meanwhile Natalia Smith was calling her father to let him know she was going to Bolivia. There didn't seem to be anyone home so she left a message. Back at the table, the three of us began to talk about random things.

Airports

Airports are incredibly unusual places in that you're literally nowhere, especially once you've moved passed the "security" area. You're no longer really in the city of departure and you're not exactly at your place of destination either, and you're in what is essentially a holding cell. You can't go anywhere, time is relative. Planes become like beacons of hope (you stare at them with awe through the window), and only one of them will take you safely out if this nowhere place and back into lineal time in the real world. So, the only truth that exists is making sure you get on your plane.

Everything in an airport, therefore, is extremely controlled, everybody sits very close to the gate, waiting, sometimes eating donuts and coffee, sometimes shopping at the duty free, but always with one foot at the gate, wouldn't want to miss your reason to exist! Everything is clean and well organized. Sometimes you run into people who actually work there, cleaning or selling "travel items", and you automatically feel sorry for them because they're forced to remain nowhere for such a long time. And you know that this safety line between passengers and their planes, which holds people together and prevents chaos from ensuing, is incredibly fragile. You know this as soon as this line is slightly altered in some way.

You hear a mysteriously soothing female voice, as if God herself were talking to you personally, and this voice kindly tells you that your gate has been changed to another gate which automatically sounds distant, unfamiliar, exotic even. Well, that's when you start to panic. As if you've already lost your plane!

"No chance in hell I'm gonna find this mysterious new gate!"

People at this point enter into a state of delirium and start to do things they don't usually do, like talk to other people or run. The plane! What will become of me!?

Waiting for Guffman?

Latin America has been in an airport holding cell for quite a long time. It is not exactly traditional (pre-industrial, pre-economic, underdeveloped, or primitive), but it's also not exactly modern (industrial, advanced or developed). It is nowhere. The only thing it knows is that it has to get on an airplane that will transport it to the beautiful destination shown on the monitors throughout the airport. There are signs everywhere, some are in English, some in Chinese, others in Russian, they all explain just how to get to the correct gate. But Latin America, who happens to be a good listener, has followed them all and has never made it. It sits next to a Dunkin Donuts waiting for the next announcement and the next set of instructions.

What if there is no gate? What if there is no plane? What if Dunkin Donuts, Starbucks Coffee and gift shops is as good as it gets?

I wonder if it's a coincidence that airport holding cells are looking more and more like American Malls. It might not be. In any case, Natalia Smith, Tomas Dinges and I are heading to Bolivia, a country that has been robbed, beaten, and raped while waiting around for its connection. Judging by the reports, it seems as if Bolivians have finally decided to find a different mode of transportation. Perhaps their buses are getting dirtier and the smell of urine is intensifying as the driver turns corners a little too violently, but at least they seem to be going places, and everybody seems to have an equal shot at getting on board even if there aren't any seats left.

Monday, August 21, 2006

Bolivia: Fugaz Pero Notable

Anthony Rauld

Santiago, Chile

Wednesday, April 19, 2006

Thursday, March 30, 2006

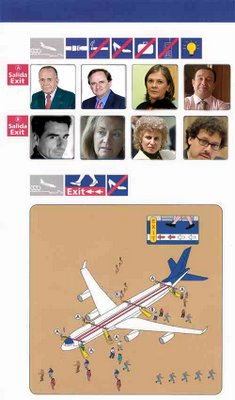

Honey I Shrunk Bachelet and Some of Her Cabinet People!

To the dismay of Chileans and the international community, the president of Chile, Michelle Bachelet, sufferred a major political setback yesterday when along with key cabinet members she was accidentally shrunk to about 0.03 percent of her original size. The incident ocurred during a coordination meeting, in the president's back yard, reportedly held to prevent further communication lapses such as the recent premature declarations involving the "morning after" pill by the Minister of Health. Eye-witnesses claim to have seen a dorky scientist played by Rick Moranis leaving the president's home shortly after the incident. Government spokesman Ricardo Lagos Weber said in a news conference this morning that the president would now be changing her governing style. In response to a question by a reporter, Lagos said that President Bachelet "is now closer to the ground than she ever was, but is a little afraid of giant insects."

To the dismay of Chileans and the international community, the president of Chile, Michelle Bachelet, sufferred a major political setback yesterday when along with key cabinet members she was accidentally shrunk to about 0.03 percent of her original size. The incident ocurred during a coordination meeting, in the president's back yard, reportedly held to prevent further communication lapses such as the recent premature declarations involving the "morning after" pill by the Minister of Health. Eye-witnesses claim to have seen a dorky scientist played by Rick Moranis leaving the president's home shortly after the incident. Government spokesman Ricardo Lagos Weber said in a news conference this morning that the president would now be changing her governing style. In response to a question by a reporter, Lagos said that President Bachelet "is now closer to the ground than she ever was, but is a little afraid of giant insects."

Tuesday, March 28, 2006

Get Over the Nationalism

And Chileans, who have the sea in their hearts, love the coast so much that they all live in Santiago, a smog-trapped city hidden deep in a valley, a hundred miles from the Pacific Ocean. Their passion for the sea is so strong that they break away from their dead-end jobs every chance they get. And boy do they love the coast. For ten days every year, the entire country travels a hundred miles to the same beach, at the same time. It’s quite a sight! The love for the sea is so strong that they must share the experience with thousands of their fellow patriots. From Santiago to the coast, hand in hand, on the highway. Nothing will stop them! Not even the highway authorities who see them coming and try to “dissuade” them by doubling the toll.

But it’s a small price to pay for that first glimpse of the Pacific Ocean blue. It’s true that sitting on the beach, surrounded by millions of people tends to limit your viewing of the sea, but nothing can prevent the orgasmic feeling achieved once inside the ocean. The curious thing is that about two thirds of Chileans are actually afraid of the water; they experience a pure form of terror at the thought of actually going in. For them, it’s enough to stick a foot inside; enough to realize that it’s too cold and that it’s time to head back to Santiago. For those who actually make it inside, they don’t last too long either. It’s too salty, the waves aren’t big enough, and they get sick of having to maneuver around gringos and their local followers who choose to swim around with big slabs of wood under their bodies. The love for the ocean is experienced so strongly by Chileans that they are willing to endure days and days of pointlessly cruel suffering in the form of: screaming children, sand in the face, unexpected toe-trash discovery, back-knee sunburn, ad-banner airplane flyovers, the smell of boiled egg, unqualified swimwear, the parking mafia, the come-out-of-nowhere car shade provider who doubles as the beach paddle salesman, the painful realization that you’re not at the “cool” beach, the “sabotage” ice cream purchase that seals your fate as “sticky hands” for the rest of the day, overtly undersized beach towels, the sudden flatlining of your Discman, etc.

All this, a nightmare! And yet for every Chilean, the thought of visiting the beach brings a smile to their face. Such unconditional love cannot be challenged, it is almost genetic. Not even the Bolivians can get too close.

It turns out, unsurprisingly, that Bolivians also love the sea. The only problem is that they don’t have any. They lost their access to the sea as a result of a 18th century war instigated by the British empire as part of a Pinky and the Brain scheme to gain control of the massive nitrate deposits in the North of what is now Chile. Not only does Bolivia have difficulties trying to export anything, they actually have to carry a passport in order to go to the beach! With a new president, one that actually looks Bolivian, Chile’s neighbor is now in a position to negotiate bilaterally with Chile, and perhaps unilaterally with other Latin American nations, sovereign access to the Pacific Ocean. The plan calls for a corridor running parallel with the Chile-Peru border, just north of Arica.

Meanwhile, Chileans, who are now safely back in their homes in Santiago, their two-week nightmare experience at the beach already forgotten, suddenly go ape-shit nationalistic. Why should we give them a centimeter of our beaches? Those beaches belong to Chile! The national anthem is bellowing in the background as every conceivable racist and classist remark is uttered. Bolivians shouldn’t get shit! Bolivians are trying to blame us for their poverty! Bolivians are backward monkeys! Bolivians should go fuck themselves! It’s OUR territory, WE’RE not gonna give them shit! These are people, mind you, who’ve never even been to Arica, and they don’t have the faintest idea what Chile even looks like further up north. And here is where Chilean mediocrity shines through. These Chileans who turn to the worst kind of slander in order to express a confused nationalism, one that doesn’t square with the reality of their country, are the same Chileans whose only option in this world is to sell their labor for miserable wages directly or indirectly to companies that if not completely foreign are controlled by foreign interests.

These foreign interests, expressed euphemistically by economists as “foreign investment” coupled with “economic stability”, control a large majority of all the economic activity in Chile; increasingly so, this translates into the control of all human activity here. Where they shop, what they buy, how they pay, who they work for, how much they get paid, in what model subway train they will travel, in what style of elevator they will elevate in, what to think about, what to exercise in, at what to laugh at, at what to cry about, at what appliance to gawk at, what to fill their tanks with, etc. What this means, essentially, is that Chile, besides being the economic model cited by the Wall Street Journal, is also a country that has sold its people, their labor, their minds and all the other natural and cultural wonders, much like a supermarket sells its entrails; in other words, to whomever will pay. So the question that follows is: What Chile are you trying to save from falling into the hands of the Bolivians? What is there left to hand over? Will anyone object when they remove the star on the Chilean flag and replace it with the Shell logo?

Do you think History will judge those Chileans who would want to help a brother in need and at the same time discover that they themselves are also in need, before it’s too late? How exactly are Chileans going to see the latest foreign movie, or shop for those modern foreign products, or eat at the scientifically designed foreign fast-food chains if people at home don’t have the electricity to turn on the television, or if the box stores can’t turn the lights on inside, or if the franchise owners can’t keep the microwaves going. The truth is that, much sooner than later, Chile won’t be able to turn the Christmas lights on because it doesn’t have any natural gas, or any other reliable source of energy. Guess who has plenty of it?

Chileans need a reality check. The confusion could be seen when the President of Chile awarded Bono a charango as a symbol of Chilean culture. The charango is much more Bolivian than it is Chilean. If it weren’t for Horacio Duran, Chileans wouldn’t have the slightest idea as to what a charango was, and most of them don’t have the slightest idea who Horacio Durango is. I think it would be better for Chileans to get over the nationalism and focus on recovering their country from foreign capital. But the way they’re going, it would be better to hand over that beach to the Bolivians as quickly as possible before foreign investors decide to build some monstrous vacation resort there or turn it into a toxic waste disposal site.

Friday, March 03, 2006

A Mapuche Radio Program in Santiago

Powered by Castpost

Summary of the Project

Wixage Anai (working title) is a documentary project, of which the above video is only a glimpse, which examines the future of indigenous media in Latin America, specifically in the urban metropolis of Santiago, Chile. Centered around the everyday existence of a Mapuche radio production, this audiovisual poject attempts to shed light on some of the experiences and challenges Mapuches face in their important struggle to reaffirm both their culture and their political rights in a culturally and politically difficult environment. This struggle takes place in the capital city of a country famous for its adoption of a neoliberal economic model where the mass media, which is concentrated in the hands of a few economic holdings, plays an important role in reproducing an apolitical society fixated on economic growth. The project sets out to answer how alternative media, representing different visions and cosmovisions, can help broaden the horizons of such a rigid paradigm of economic development and help create a true democracy not only in Chile, but throughout the world.

Project Goals

1. Promote awareness about Mapuche experiences in the city.

2. Address and dispel popular misconceptions about Mapuches.

3. Generate a critical perspective on the mass media.

4. Show some of the production's technical and cultural difficulties.

5. Show how the two cosmovisions (Mapuche and Occidental) clash in a city landscape.

6. Raise funds for the continuation of the program Wixae Anai.

7. Generate enthusiasm for alternative media in young people.

8. Show positive images of Mapuches in Chilean media.

Introduction

The Mapuche people of Chile are seen by the majority of Chileans in Santiago as relics of the past, as statues erected out of clay and summoned for this month’s museum exhibit. Their images are unmoving, frozen in time for citizens of the modern state to consume as art or entertainment. They represent a discarded way of life labeled “traditional”, and although many of their cultural artifacts, especially their silver jewelry work, are cherished for their undisputed value, the Mapuche people, as a rule, are discriminated against in all sectors of contemporary society, and even by themselves. But even as we read about this harsh reality, the Mapuche are regaining their voice and are teaching each other many of the cultural elements that have been lost to the often violent process of colonization, modernization and economization. Especially in Santiago, this phenomenon represents a struggle of enormous magnitude, a cultural movement that, among other things, pretends to teach young generations how to stand up in the world, how to resist the self-degradation encouraged by the market system, and how to simply be proud of themselves along with their communities. It is unfortunate that the public opinion in Chile simply discards this cultural struggle and is stubborn in its adopted market rationality, which prevents interpreting the Mapuche as anything other than poor Chileans who are underdeveloped and in need of technical assistance, or sometimes as violent terrorists who represent an unclear threat to the elusive development of the country.

The Mapuche people of Chile are seen by the majority of Chileans in Santiago as relics of the past, as statues erected out of clay and summoned for this month’s museum exhibit. Their images are unmoving, frozen in time for citizens of the modern state to consume as art or entertainment. They represent a discarded way of life labeled “traditional”, and although many of their cultural artifacts, especially their silver jewelry work, are cherished for their undisputed value, the Mapuche people, as a rule, are discriminated against in all sectors of contemporary society, and even by themselves. But even as we read about this harsh reality, the Mapuche are regaining their voice and are teaching each other many of the cultural elements that have been lost to the often violent process of colonization, modernization and economization. Especially in Santiago, this phenomenon represents a struggle of enormous magnitude, a cultural movement that, among other things, pretends to teach young generations how to stand up in the world, how to resist the self-degradation encouraged by the market system, and how to simply be proud of themselves along with their communities. It is unfortunate that the public opinion in Chile simply discards this cultural struggle and is stubborn in its adopted market rationality, which prevents interpreting the Mapuche as anything other than poor Chileans who are underdeveloped and in need of technical assistance, or sometimes as violent terrorists who represent an unclear threat to the elusive development of the country. One explanation for this unwillingness to respect or lend credibility to this movement is that it has the potential to call into question something that, for better or worse, has been tacitly adopted by the Chilean economic and political establishment. The post-pinochet “flowering” of the modern market system in Chile has facilitated the importation of a “disposable” culture of production and consumption into the country. Along with its key cultural elements (individuation, indifference, excess consumption of resources by a minority, the tacit acceptance of a watered-down electoral democracy, privatization, the adoption of the discourse of economic “growth” as substitute for social justice, a stubborn insistence on the word “development” even though the idea behind it is dead, labor mistreatment as competition, greed, the adoption of American culture, etc), is almost by definition the antithesis of mapuche culture. It is true that in Santiago, people who define themselves as mapuche, share and practice many, if not most, of the same values and habits that every other Chilean does (almost out of shear necessity); but this cultural movement is beginning to tilt the boat in another direction. While the neoliberal economic model sponsored by the Chilean government is being elevated to the status of a religion and questioned only by a few heretics, the Chilean state is losing a considerable portion of the population to an idea, to a way of seeing the world, that is incompatible with the homogeneity that it requires for the continued implementation of the economic model. Exploring the different ways in which the mapuche culture, and its “re-awakening”, represents a big question mark for the dominant market culture is essential. How does the mapuche culture problematize the modern industrial way of life here in Chile?

One explanation for this unwillingness to respect or lend credibility to this movement is that it has the potential to call into question something that, for better or worse, has been tacitly adopted by the Chilean economic and political establishment. The post-pinochet “flowering” of the modern market system in Chile has facilitated the importation of a “disposable” culture of production and consumption into the country. Along with its key cultural elements (individuation, indifference, excess consumption of resources by a minority, the tacit acceptance of a watered-down electoral democracy, privatization, the adoption of the discourse of economic “growth” as substitute for social justice, a stubborn insistence on the word “development” even though the idea behind it is dead, labor mistreatment as competition, greed, the adoption of American culture, etc), is almost by definition the antithesis of mapuche culture. It is true that in Santiago, people who define themselves as mapuche, share and practice many, if not most, of the same values and habits that every other Chilean does (almost out of shear necessity); but this cultural movement is beginning to tilt the boat in another direction. While the neoliberal economic model sponsored by the Chilean government is being elevated to the status of a religion and questioned only by a few heretics, the Chilean state is losing a considerable portion of the population to an idea, to a way of seeing the world, that is incompatible with the homogeneity that it requires for the continued implementation of the economic model. Exploring the different ways in which the mapuche culture, and its “re-awakening”, represents a big question mark for the dominant market culture is essential. How does the mapuche culture problematize the modern industrial way of life here in Chile?Representation

In the late 1990’s and early 2000, images of masked Mapuches with slings dominated the mainstream press and rarely were they accompanied by representations of the extensive repression exercised by the Chilean carabineros and local paramilitaries (associated with land-owners) in response to what many important scholars and human rights authorities consider to be legitimate land claims made by various Mapuche organizations. As is usual in the dominant commercial media, real context is discarded in favor of simplistic and sensational appeals for ratings (“viewership”), usually constructed on the basis of fear. The Mapuche activists, the organizations they represented, and the communities represented by their organizations were lumped together into a nutshell labeled something like “disgruntled”, “pissed-off”, or “highly upset”. About what? Who knew? The context, the complicated history of the land issue, including the political and legal maneuverings (and decrees) associated with the transfer of land from families to private conglomerates, are not as easy to edit down into a headliner or a sound byte. Neither are the long history of intervention by distinct authorities into ancestral lands and the violent expropriation of the same. In those tense moments, public opinion about the Mapuche, needless to say, went from indifferent to contemptuous. This “intifada”, as one major newspaper headline read, brings up the unavoidable link that exists within this movement between the cultural and the political. That is to say, territory is an integral part of the traditional Mapuche culture, historically defined, administered and even granted legitimacy by the Spanish crown, the ancestral territory, and now its recuperation, form an important part of the Mapuche movement. Obviously, this troubles the Chilean government, who is forced to juggle interests of varying dimensions, including hydroelectric projects, massive tree farming, and agricultural development, all key ingredients in the neoliberal export-model.

In the late 1990’s and early 2000, images of masked Mapuches with slings dominated the mainstream press and rarely were they accompanied by representations of the extensive repression exercised by the Chilean carabineros and local paramilitaries (associated with land-owners) in response to what many important scholars and human rights authorities consider to be legitimate land claims made by various Mapuche organizations. As is usual in the dominant commercial media, real context is discarded in favor of simplistic and sensational appeals for ratings (“viewership”), usually constructed on the basis of fear. The Mapuche activists, the organizations they represented, and the communities represented by their organizations were lumped together into a nutshell labeled something like “disgruntled”, “pissed-off”, or “highly upset”. About what? Who knew? The context, the complicated history of the land issue, including the political and legal maneuverings (and decrees) associated with the transfer of land from families to private conglomerates, are not as easy to edit down into a headliner or a sound byte. Neither are the long history of intervention by distinct authorities into ancestral lands and the violent expropriation of the same. In those tense moments, public opinion about the Mapuche, needless to say, went from indifferent to contemptuous. This “intifada”, as one major newspaper headline read, brings up the unavoidable link that exists within this movement between the cultural and the political. That is to say, territory is an integral part of the traditional Mapuche culture, historically defined, administered and even granted legitimacy by the Spanish crown, the ancestral territory, and now its recuperation, form an important part of the Mapuche movement. Obviously, this troubles the Chilean government, who is forced to juggle interests of varying dimensions, including hydroelectric projects, massive tree farming, and agricultural development, all key ingredients in the neoliberal export-model. The “historical warrior” Mapuche forms part of the Chilean foundation of pride and strength taught in schools across the nation. The Mapuche, lead by mythical figures representing stamina and cunning wit, managed to halt the southern advance of the Spanish conquistadores. Mapuches of today, however, are nevertheless expected to cede the way for the great industrial machine of progress and civilization. Any continued resistance to “invaders” is not only inappropriate, but it is also illogical from the point of view of the dominant culture, whose economic cosmovision of “growth” and “development” is considered to be more universal and natural than gravity itself.

The “historical warrior” Mapuche forms part of the Chilean foundation of pride and strength taught in schools across the nation. The Mapuche, lead by mythical figures representing stamina and cunning wit, managed to halt the southern advance of the Spanish conquistadores. Mapuches of today, however, are nevertheless expected to cede the way for the great industrial machine of progress and civilization. Any continued resistance to “invaders” is not only inappropriate, but it is also illogical from the point of view of the dominant culture, whose economic cosmovision of “growth” and “development” is considered to be more universal and natural than gravity itself.The Media

What role does the media play? At the risk of sounding dramatic, the media is one of the key players in all of this because it is the media who determines what is real and what isn't. It is clear that the Mapuches exist little, and perhaps this media indifference echoes the government’s inability to grant the Mapuche constitutional recognition, or perhaps its inability to sign the International Labor Organization’s convention 169 on indigenous rights. When the Mapuches do appear from the dark recesses of oblivion, it is only to fill the role of the disgruntled citizen who represents a clear and present danger to the march of development towards progress. The conflict between Mapuche activists, the Chilean state, and transnational business firms is characterized not as a government problem, or an economic problem, but rather as “the mapuche problem”. Partly because the loss of land and territory is buried in the past and rendered invisible by the nature of incremental change, the media is simply unable to present the issue as anything other than a temporary imbalance that must be dealt with criminally, inviting viewers to, in the meantime, think little and do nothing until the storm passes. How is this level of indifference cultivated and maintained?

What role does the media play? At the risk of sounding dramatic, the media is one of the key players in all of this because it is the media who determines what is real and what isn't. It is clear that the Mapuches exist little, and perhaps this media indifference echoes the government’s inability to grant the Mapuche constitutional recognition, or perhaps its inability to sign the International Labor Organization’s convention 169 on indigenous rights. When the Mapuches do appear from the dark recesses of oblivion, it is only to fill the role of the disgruntled citizen who represents a clear and present danger to the march of development towards progress. The conflict between Mapuche activists, the Chilean state, and transnational business firms is characterized not as a government problem, or an economic problem, but rather as “the mapuche problem”. Partly because the loss of land and territory is buried in the past and rendered invisible by the nature of incremental change, the media is simply unable to present the issue as anything other than a temporary imbalance that must be dealt with criminally, inviting viewers to, in the meantime, think little and do nothing until the storm passes. How is this level of indifference cultivated and maintained? Societies have become so big and complex, and people/families have become so individuated and isolated (ironically), that their perception of the world beyond their doorstep, or beyond their physical and immediate reach is determined solely on the benevolent service of the mass media. This is alarmingly so in Chile where the majority of people perceive their country and the world through the eyes and ears of a handful of media conglomerates which represent the beliefs of the economic establishment and their obsessive interest in economic stability, depoliticization, and potential for economic “growth” pegged to the globalization model. The centralization of the media system helps to manufacture a narrow representation of reality, a reality which leaves little room for alternative or conflicting visions. Is it too outrageous to suggest that the reality constructed by a handful of media conglomerates, who depend on the success of their sponsors for their own survival, might be a little biased towards the interests of the economic establishment? The enormous development investments that are present in the south, all of which represent a unified gamble on the stability of those key regions where the largest percentage of Mapuches live, constitute a huge lobby; it is disingenuous to deny that there is a fundamental correlation between the media construction, or outright dismissal of the Mapuche land issue and the economic interests that might be affected by indigenous claims to ancestral territory. Hence what we see is a flagrant misrepresentation, or non-representation of, not only the Mapuche movement, but of any social movement representing legitimate claims and worries associated with the neoliberal economic model. The environment, inequality, violence, indifference, employment security, poverty, intolerance, and even the status of democracy are just a few issues that trouble, on a day to day level, a substantial portion of the population in Chile.

Societies have become so big and complex, and people/families have become so individuated and isolated (ironically), that their perception of the world beyond their doorstep, or beyond their physical and immediate reach is determined solely on the benevolent service of the mass media. This is alarmingly so in Chile where the majority of people perceive their country and the world through the eyes and ears of a handful of media conglomerates which represent the beliefs of the economic establishment and their obsessive interest in economic stability, depoliticization, and potential for economic “growth” pegged to the globalization model. The centralization of the media system helps to manufacture a narrow representation of reality, a reality which leaves little room for alternative or conflicting visions. Is it too outrageous to suggest that the reality constructed by a handful of media conglomerates, who depend on the success of their sponsors for their own survival, might be a little biased towards the interests of the economic establishment? The enormous development investments that are present in the south, all of which represent a unified gamble on the stability of those key regions where the largest percentage of Mapuches live, constitute a huge lobby; it is disingenuous to deny that there is a fundamental correlation between the media construction, or outright dismissal of the Mapuche land issue and the economic interests that might be affected by indigenous claims to ancestral territory. Hence what we see is a flagrant misrepresentation, or non-representation of, not only the Mapuche movement, but of any social movement representing legitimate claims and worries associated with the neoliberal economic model. The environment, inequality, violence, indifference, employment security, poverty, intolerance, and even the status of democracy are just a few issues that trouble, on a day to day level, a substantial portion of the population in Chile.Wixage Anai

The Wixage Anai documentary project, still in its early stages, is an attempt to shake the foundations of such a rigid and limited structure of representations constructed by the dominant system of media and representation. Mapuches are not warriors of the past, frozen in time, holding on to the last vestiges of “the old ways” with the help of anthropologists and museum archivists. They are very much part of a living, dynamic transformation that is occurring in the capital city of Santiago. They are creating their own representations of themselves and of the dominant Winka (occidental) cultural discourse. Embedded in an economic model that seeks to integrate Chilean resources (both human and natural) into the global economy under the banner of linear, short-term growth, perhaps this Mapuche “awakening” can also be an awakening for all Chileans, before it’s too late, before everything is lost to the all-consuming marketplace.

The Wixage Anai documentary project, still in its early stages, is an attempt to shake the foundations of such a rigid and limited structure of representations constructed by the dominant system of media and representation. Mapuches are not warriors of the past, frozen in time, holding on to the last vestiges of “the old ways” with the help of anthropologists and museum archivists. They are very much part of a living, dynamic transformation that is occurring in the capital city of Santiago. They are creating their own representations of themselves and of the dominant Winka (occidental) cultural discourse. Embedded in an economic model that seeks to integrate Chilean resources (both human and natural) into the global economy under the banner of linear, short-term growth, perhaps this Mapuche “awakening” can also be an awakening for all Chileans, before it’s too late, before everything is lost to the all-consuming marketplace.Wixage Anai focuses on a Mapuche radio program of the same name that is breaking the barriers of radial communication. As a primer for Mapuche culture in Santiago, the program is a precise example of a counter-discourse aimed at rescuing listeners from the representations monopolized by large media conglomerates that communicate solely commercial values and reinforce the corporate vision for Chile. The project centers on both the physical and abstract space of the radio program, which broadcasts primarily from a community-sponsored AM radio station (radiotierra.cl) in Bella Vista, Santiago. The radio program is produced by a Mapuche organization called Jvken Mapu, which is a communications center located in a neighborhood called Cerro Navia. The documentary project sets out to answer three fundamental questions. The first one has to do with the potential for alternative, listener-sponsored, media to play an important role in indigenous movements (in both cultural and political aspects) that are taking place in the urban centers of Latin America. In other words, what role might they play in the development of indigenous movements? The second question can be posited as follows: to what extent can alternative “discourses” representing indigenous value-systems call into question the tacit assumptions inherent in the dominant market culture? Lastly, and within the framework of alternative media, to what extent does the mass media manufacture consent in Chile and could alternative media outlets like Wixage Anai challenge this level of consent?

Thursday, March 02, 2006

Farandula In Viña

This event, which stretches for what seems like an eternity during the last week of the month, is a media intense and heavily scripted “explosion” of excitement. Various competitions are held in different music categories where international unknowns display their talents to a hopelessly bored audience of many thousands (this audience is referred to as “the beast”, supposedly for their total lack of mercy). Sprinkled in between the competition acts are various “big name” acts with small names who are invited to perform on stage. This is what makes the festival watchable…for many. All of this takes place in Viña del Mar, a city only a few miles from Valparaiso, historical port town in Chile’s fifth region. Local television is literally colonized by anything having to do with the event. Who’s coming, who’s not, who’s wearing the thing, who’s not wearing much, who’s showing more of their left breast, whose ass is firmer, and of course, who’s saying what about the others who also said some stuff earlier. It’s very much like what you’d get if you mixed the hoopla of the Oscars and the Grammy’s with a live multi-act concert and then removed anything that might be of interest.

This event, which stretches for what seems like an eternity during the last week of the month, is a media intense and heavily scripted “explosion” of excitement. Various competitions are held in different music categories where international unknowns display their talents to a hopelessly bored audience of many thousands (this audience is referred to as “the beast”, supposedly for their total lack of mercy). Sprinkled in between the competition acts are various “big name” acts with small names who are invited to perform on stage. This is what makes the festival watchable…for many. All of this takes place in Viña del Mar, a city only a few miles from Valparaiso, historical port town in Chile’s fifth region. Local television is literally colonized by anything having to do with the event. Who’s coming, who’s not, who’s wearing the thing, who’s not wearing much, who’s showing more of their left breast, whose ass is firmer, and of course, who’s saying what about the others who also said some stuff earlier. It’s very much like what you’d get if you mixed the hoopla of the Oscars and the Grammy’s with a live multi-act concert and then removed anything that might be of interest.

Of course, for Chileans, the festival is where their own "celebrities" come out and stroll onto the red carpet, and therefore the actual event is permeated with a special dreamy aura of glamour, fashion, idolatry, and showmanship, at least that's the impression one gets watching it on TV. On the ground, it's clear that the hype surrounding the event is just an elaborate farce created to hypnotize and sell as much bullshit as humanly possible and as quickly as possible, an environment ripe for making lots of money; from the power-soft drinks, the nescafe instant iced coffee, the instant tooth whitening kit, the newest hair-styling products, the latest digital music gadget, and the next modern shaving appliance…to the designer labels, entertainment acts, music records, films, silicone breasts, and television time slots. Because the cameras are always on during the "Viña party" and the entire country is watching and sucking in every last detail, the marketeers descend with their fresh marketing claws and flock to the “show” like flies on shit. But for the multitude of "fans" sitting outside the "star-packed" O'Higgins Hotel, the festival hype must appear to be something real. The excitement is genuine, the fans are physically present just outside the carefully designed media cage, the place where these consumers of dreams converge with the illusory products displayed by the farandula industry. “Farandula” literally means “a gang of homeless comedians”. Here in Chile, when you say the word “farandula” you’re probably referring to anything having to do with celebrities. The farandula industry is a relatively new phenomenon in Chile, but it is a rapidly growing industry that capitalizes on the curiosity of home viewers in relation to the rich and famous. The foot soldiers in the farandula industry are the “journalists” who make a living spewing whatever “information” their producers or editors deem marketable, or whatever information might be of interest to an imagined viewer. For example, an actress in a soap opera is dating the producer but doesn’t want to admit it, or the conductor of a program was seen holding hands with an Argentinean model at a closed party. The consumers of the farandula industry are always imagined by its producers to be desperate hoards in need of whatever gossip is available about famous people. Although it may be true that television viewers will suck on anything that’s put in front of them, this is strictly a one-way highway of information where the industry decides what it is that they should suck on. The curious thing, of course, is that the farandula “reporting” just happens to increase ratings as well as the overall success rates of the productions associated with the celebrity subjects. It goes without saying that most of the content that is “reported’ is elaborately planned ahead of time with this in mind.