Spot Festival Cine Valdivia 2006

Thursday, September 21, 2006

Monday, September 11, 2006

Festival de Valdivia: Part IV

Lo Mas Bonito y Mis Mejores Años

Having gone to Bolivia the week before the festival and after having been immersed, at least for an instant, in the political process which is unfolding there, the Bolivian film Lo Mas Bonito y Mis Mejores Años (The Most Beautiful Things and My Best Years), became a natural draw for me. On the Lord Cochrane stage appeared this twenty five year old cochabambino named Martin Boulocq: long hair, Spanish features, dress jacket, jeans, and sneakers. While timidly presenting his film, he promises to come back at the end to answer questions.

The film begins. It takes place in Cochabamba, Bolivia, a city which became famous internationally a few years back when mass protests successfully thwarted the privatization of the public water supply. It is an urban landscape that has obviously suffered years of neglect. Immediately, we get the impression that this is some sort of a documentary. The dialogue, although almost inexistent, is very realistic, and the scene is filmed hap hazardously, coming in and out of focus with jolty frames, camera angles and distances that defy convention, the sound of the street outside is picked up as is a noticeable room tone. Someone works in a video rental place and for what seems like an eternity, nobody really says anything. Someone is trying to sell a car? You can't really tell. Slowly, we begin to situate ourselves in this gritty urban world and come to recognize our main characters. Before this happens, however, several people have already left the theatre.

Visually, it is definitely an acquired taste. Much more interesting is the way Boulocq approaches his film. Apparently, with no script (not one piece of paper) and with only a vague idea as to the structure of the story, the director places his cast and crew into a variety of concrete situations where improvisation is the rule. None of the actors knew what was supposed to take place and they were only supplied with concrete situations where they would have to improvise, not knowing what the other actor might do. It is somewhat similar to the way Sebastian Campos (Chilean director graduated from the Escuela de Cine in Santiago) directed La Sagrada Familia. The attempt was made to document a piece of "provoked reality". As such, the film can be considered a documentary as well as an instance of fiction. Excellent film editing by Guillermina Zabala.

The story is simple but very revealing. The quiet and bearded Berdo is looking for a way out of Cochabamba and in order to pay for his ticket, he has decided to sell his 65 Volkswagen, which eventually becomes the audience's main vehicle around the disturbed city. Victor, a video store clerk, becomes his best friend and helps him in the campaign to sell the car. Although they share a lot of time together, it is Victor who doses most of the talking and persuading, while Berdo, who is a very quiet and timid young man, passively absorbs his philosophical ranting. Victor is a troubled cochabambino, plagued with the impossibility of his projects and dreams. The only two things that are keeping Berdo from committing suicide, it seems, are Victor's "teachings" and the possibility of leaving cochabamba. The arrival of Victor's girlfriend Camila saves the story from floundering but also adds to the tormentuous relationship between Victor and Berdo.

The film is about how young people who are faced with a bleak reality and an even less appealing future struggle to maintain some level of dignity. It is a groundbreaking film which indirectly tackles some of the persistent social problems in Latin America.

Having gone to Bolivia the week before the festival and after having been immersed, at least for an instant, in the political process which is unfolding there, the Bolivian film Lo Mas Bonito y Mis Mejores Años (The Most Beautiful Things and My Best Years), became a natural draw for me. On the Lord Cochrane stage appeared this twenty five year old cochabambino named Martin Boulocq: long hair, Spanish features, dress jacket, jeans, and sneakers. While timidly presenting his film, he promises to come back at the end to answer questions.

The film begins. It takes place in Cochabamba, Bolivia, a city which became famous internationally a few years back when mass protests successfully thwarted the privatization of the public water supply. It is an urban landscape that has obviously suffered years of neglect. Immediately, we get the impression that this is some sort of a documentary. The dialogue, although almost inexistent, is very realistic, and the scene is filmed hap hazardously, coming in and out of focus with jolty frames, camera angles and distances that defy convention, the sound of the street outside is picked up as is a noticeable room tone. Someone works in a video rental place and for what seems like an eternity, nobody really says anything. Someone is trying to sell a car? You can't really tell. Slowly, we begin to situate ourselves in this gritty urban world and come to recognize our main characters. Before this happens, however, several people have already left the theatre.

Visually, it is definitely an acquired taste. Much more interesting is the way Boulocq approaches his film. Apparently, with no script (not one piece of paper) and with only a vague idea as to the structure of the story, the director places his cast and crew into a variety of concrete situations where improvisation is the rule. None of the actors knew what was supposed to take place and they were only supplied with concrete situations where they would have to improvise, not knowing what the other actor might do. It is somewhat similar to the way Sebastian Campos (Chilean director graduated from the Escuela de Cine in Santiago) directed La Sagrada Familia. The attempt was made to document a piece of "provoked reality". As such, the film can be considered a documentary as well as an instance of fiction. Excellent film editing by Guillermina Zabala.

The story is simple but very revealing. The quiet and bearded Berdo is looking for a way out of Cochabamba and in order to pay for his ticket, he has decided to sell his 65 Volkswagen, which eventually becomes the audience's main vehicle around the disturbed city. Victor, a video store clerk, becomes his best friend and helps him in the campaign to sell the car. Although they share a lot of time together, it is Victor who doses most of the talking and persuading, while Berdo, who is a very quiet and timid young man, passively absorbs his philosophical ranting. Victor is a troubled cochabambino, plagued with the impossibility of his projects and dreams. The only two things that are keeping Berdo from committing suicide, it seems, are Victor's "teachings" and the possibility of leaving cochabamba. The arrival of Victor's girlfriend Camila saves the story from floundering but also adds to the tormentuous relationship between Victor and Berdo.

The film is about how young people who are faced with a bleak reality and an even less appealing future struggle to maintain some level of dignity. It is a groundbreaking film which indirectly tackles some of the persistent social problems in Latin America.

Friday, September 08, 2006

Festival de Valdivia 2006: PART III

Sunday was marked by two non-film related events: eating a delicious baked sierra fish with white wine and playing a pichanga (impromptu and informal soccer with a poorly defined playing field, with ad-hoc goals and usually involving lots of dirt or holes) with some students we had met earlier down the road in front of a nearby cabin. These cabins, by the way, were complete with a wood fireplace, porch, cable and maid service. For only twenty five thousand pesos a night, not bad deal.

The Austral University students were tremendous Pink Floyd fans, singing and mumbling the words to typical Pink Floyd songs while strumming on their guitars in front of their porch; they seemed to be living in some fairy tale world, just relaxing and playing music in the shadow of their rustic cabin. We woke them up a little with our city enthusiasm and I played some annoying Radiohead for them. They seemed to appreciate it.

We re-entered the world of films soon after. It was late afternoon by the time I made it to the Austral campus, where two of the festival's screens were located (just on the other side of the Valdivia river), the documentary about the Mapuche had already started. The film, called We Pu Liwen (New Dawn) and directed by Francisco Toro Lessen, was your typical film about Mapuches and there was very little that could be rescued. The importance of mapuche culture, the struggle to maintain mapuche identity alive, etc.

This specific documentary focused on the Mapuche Cosmovision and included poetry by Lorenzo Aillapan. The problem with these documentaries is that the Mapuches depicted tend to automatically revert to a very rehearsed discourse about their identity and the struggle to keep it alive. At no point do we feel that we really understand the subjects better or that we are closer to them as a result of the exposition. Quite frankly, images of mapuches with their ponchos walking through the wilderness flanked by the sounds of the kultrun and the trutruca have become quite cliché and it's not clear whether they contribute anything new to the mapuche documentary genre. Sometimes it's important to expose the subject's own discourse and not just take it at face value.

The best of Sunday, we thought, would be reserved for the Chilean premiere of Almodovar's latest film, Volver (Return). This was clearly the public's favorite. Penelope Cruz was scheduled to present the film, but for some reason, she didn't show up and the supporting actress, Lola Duenas, presented the film instead. There were a lot of cameras hovering over the "almodovar girl" and the intense light they were constantly beaming on her while could only have been annoying. The Lord Cochrane theatre, where most of the competing films were screened, was overflowing with people and we could sense the intense hype surrounding the film.

Of course, a film with semejante level of hype can only become a let-down. Surprisingly, however, there are quite a few things that made Volver, Almodovar's latest festival winner, worth remembering. For one thing, Penelope Cruz. It is truly remarkable to watch and hear her move around the screen. She is in constant motion, both physically and emotionally. While in one minute her face explodes in laughter as she prances around an equally colorful interior, in another it reveals a precise level of panic and fear as she tries to cope with the complicated realization that her daughter has killed her husband.

All this, of course, complimented by fantastic dialogue which dominates each scene, it provides the essential energy for each character and never for a second feels forced. Completely spontaneous. And never do we doubt for a second that Penelope Cruz is Raimunda, never does it occur to us that she's an actress playing a part, until, of course, the spell is broken and the film comes to an end.

More so than in other films where he clearly accentuates his female characters and fills them up to the brim with an exaggerated sense of confidence, emotion, sex appeal, intelligence and physical and intellectual panache, Almodovar really goes the extra mile to pay homage to the female race. In many interviews given around the world, he has stressed that for him, this film is a return to his childhood, which he remembers to be predominantly marked by women. Indeed, it is made clearer with Volver that his fascination for the female character, translated cinematographically into a wonderful spectrum of female color, emotion and intelligence, is what drives his filmmaking.

In Volver, men simply don't exist; they are not important, they are secondary at best and often simply fill spaces that need filling, to reaffirm their own obsolescence or to consecrate their obvious dysfunction in the world. Men are there because they played some marginal partin the creation of their daughters (often in unconventional ways), but not because they contribute or because they deserve any real screen time. In the world of Volver, Raimunda (Penelope Cruz) is alone to construct her life and to raise her daughter in spite of her husband (who is, basically, a loser imported from a different world or genre altogether). When the husband is killed off early in the film, his sudden departure from the world of the living automatically becomes a problem of what to do with the body; his absence is never interpreted as a significant loss nor seen as a tragedy in its own right.

In Volver, women are masters of their own destiny. They are hardly well organized, disciplined, overly confident (like the corporate women in El Metodo) or even emotionally or economically stable for that matter, but that doesn't necessarily translate into a loss of will or control, or the sudden interruption of a life well-lived and felt. Raimunda is a mess, she works as a sub-contracted maintenance worker in an airport, has no other clear or stable source of income (but she does stumble upon an opportunity to take over a restaurant and she doesn't hesitate for a second), she is haunted by a mysterious fire which claimed the life of her mother (whom she has a lot of unfinished business with), her sister Sole runs an illegal beauty salon out of her messy apartment, she has a daughter who doesn't know where she came from, but this never for a moment brings into question Raimunda's freedom. She works it out, then panics, relaxes again, figures it out again, devises plans, carefully calculates her options, carries out her missions, explodes in sadness again, recovers again, and all of it done with unquestionable grace (she even takes a piss on screen, again, full of grace). But never for an instant is her will challenged, her grace compromised, never for one second does she stop feeling and living a su estilo; she is the master of her domain and is never required to explain anything or give up the essential elements of being human- those elements that are so sadly repressed in men (and exaggerated in women by Almodovar).

When we think about the women in Almodovar's world and then switch over to the women in Jafar Panahi's The Circle, we might as well be talking about two different species. The interesting thing about this, especially when we consider the awesome potential films have to convey such contrasting worlds, is that we're not talking about two different species.

Jafar Panahi is a critically acclaimed Iranian director whose films deal with the realities of modern life in Iran. This year, the Valdivia Film Festival has a retrospective which brings some of his most acclaimed films to the tail end of the world for the very first time.

On the last day of the festival (and here we are obviously jumping ahead in time), Panihi presented his film The Circle which deals with the harsh realities that Iranian women have to face in post-revolution Iran. Here, urban Iranian women are depicted as defeated souls, lost in a maze of indifference, in a Tehran which brutally ostracizes and marginalizes women ("you can't go anywhere without a man"). The film takes turns following three loosely related female characters through the streets of Tehran. The first two women have been granted temporary release from prison and have no intention of returning, while a third women, whose story is casually taken up by the film towards the end, has escaped outright from prison and is desperately seeking arrangements for an illegal abortion. They frantically try to achieve their objectives, the first two wish to flee to a far away place and the pregnant woman seeks the help of old friends, but they fail to gain ground in an extremely closed society. There are many alludes to the question of freedom in Iran as well as to male domination, consequently, the film was banned there.

Comparing the treatment of women in the two films, we see immediately that there is nothing beautiful or worthwhile about the Iranian women in The Circle other than their obvious courage. One gets the impression that most of the time invested went into portraying Tehran as this terrible place full of danger and indifference at every corner, while almost no attention was dedicated to actually developing the female parts, characters who will no doubt be seen by western audiences as representing Iranian women in general. For the most part, they come across as one-dimensional and shallow. One never really feels a sense of injustice because the women never reveal their true humanity in the film. It sometimes feels as if Panihi, by forgetting to give these women personalities, is just as guilty of repressing them as the society he is trying to critique.

The Austral University students were tremendous Pink Floyd fans, singing and mumbling the words to typical Pink Floyd songs while strumming on their guitars in front of their porch; they seemed to be living in some fairy tale world, just relaxing and playing music in the shadow of their rustic cabin. We woke them up a little with our city enthusiasm and I played some annoying Radiohead for them. They seemed to appreciate it.

We re-entered the world of films soon after. It was late afternoon by the time I made it to the Austral campus, where two of the festival's screens were located (just on the other side of the Valdivia river), the documentary about the Mapuche had already started. The film, called We Pu Liwen (New Dawn) and directed by Francisco Toro Lessen, was your typical film about Mapuches and there was very little that could be rescued. The importance of mapuche culture, the struggle to maintain mapuche identity alive, etc.

This specific documentary focused on the Mapuche Cosmovision and included poetry by Lorenzo Aillapan. The problem with these documentaries is that the Mapuches depicted tend to automatically revert to a very rehearsed discourse about their identity and the struggle to keep it alive. At no point do we feel that we really understand the subjects better or that we are closer to them as a result of the exposition. Quite frankly, images of mapuches with their ponchos walking through the wilderness flanked by the sounds of the kultrun and the trutruca have become quite cliché and it's not clear whether they contribute anything new to the mapuche documentary genre. Sometimes it's important to expose the subject's own discourse and not just take it at face value.

The best of Sunday, we thought, would be reserved for the Chilean premiere of Almodovar's latest film, Volver (Return). This was clearly the public's favorite. Penelope Cruz was scheduled to present the film, but for some reason, she didn't show up and the supporting actress, Lola Duenas, presented the film instead. There were a lot of cameras hovering over the "almodovar girl" and the intense light they were constantly beaming on her while could only have been annoying. The Lord Cochrane theatre, where most of the competing films were screened, was overflowing with people and we could sense the intense hype surrounding the film.

Of course, a film with semejante level of hype can only become a let-down. Surprisingly, however, there are quite a few things that made Volver, Almodovar's latest festival winner, worth remembering. For one thing, Penelope Cruz. It is truly remarkable to watch and hear her move around the screen. She is in constant motion, both physically and emotionally. While in one minute her face explodes in laughter as she prances around an equally colorful interior, in another it reveals a precise level of panic and fear as she tries to cope with the complicated realization that her daughter has killed her husband.

All this, of course, complimented by fantastic dialogue which dominates each scene, it provides the essential energy for each character and never for a second feels forced. Completely spontaneous. And never do we doubt for a second that Penelope Cruz is Raimunda, never does it occur to us that she's an actress playing a part, until, of course, the spell is broken and the film comes to an end.

More so than in other films where he clearly accentuates his female characters and fills them up to the brim with an exaggerated sense of confidence, emotion, sex appeal, intelligence and physical and intellectual panache, Almodovar really goes the extra mile to pay homage to the female race. In many interviews given around the world, he has stressed that for him, this film is a return to his childhood, which he remembers to be predominantly marked by women. Indeed, it is made clearer with Volver that his fascination for the female character, translated cinematographically into a wonderful spectrum of female color, emotion and intelligence, is what drives his filmmaking.

In Volver, men simply don't exist; they are not important, they are secondary at best and often simply fill spaces that need filling, to reaffirm their own obsolescence or to consecrate their obvious dysfunction in the world. Men are there because they played some marginal partin the creation of their daughters (often in unconventional ways), but not because they contribute or because they deserve any real screen time. In the world of Volver, Raimunda (Penelope Cruz) is alone to construct her life and to raise her daughter in spite of her husband (who is, basically, a loser imported from a different world or genre altogether). When the husband is killed off early in the film, his sudden departure from the world of the living automatically becomes a problem of what to do with the body; his absence is never interpreted as a significant loss nor seen as a tragedy in its own right.

In Volver, women are masters of their own destiny. They are hardly well organized, disciplined, overly confident (like the corporate women in El Metodo) or even emotionally or economically stable for that matter, but that doesn't necessarily translate into a loss of will or control, or the sudden interruption of a life well-lived and felt. Raimunda is a mess, she works as a sub-contracted maintenance worker in an airport, has no other clear or stable source of income (but she does stumble upon an opportunity to take over a restaurant and she doesn't hesitate for a second), she is haunted by a mysterious fire which claimed the life of her mother (whom she has a lot of unfinished business with), her sister Sole runs an illegal beauty salon out of her messy apartment, she has a daughter who doesn't know where she came from, but this never for a moment brings into question Raimunda's freedom. She works it out, then panics, relaxes again, figures it out again, devises plans, carefully calculates her options, carries out her missions, explodes in sadness again, recovers again, and all of it done with unquestionable grace (she even takes a piss on screen, again, full of grace). But never for an instant is her will challenged, her grace compromised, never for one second does she stop feeling and living a su estilo; she is the master of her domain and is never required to explain anything or give up the essential elements of being human- those elements that are so sadly repressed in men (and exaggerated in women by Almodovar).

When we think about the women in Almodovar's world and then switch over to the women in Jafar Panahi's The Circle, we might as well be talking about two different species. The interesting thing about this, especially when we consider the awesome potential films have to convey such contrasting worlds, is that we're not talking about two different species.

Jafar Panahi is a critically acclaimed Iranian director whose films deal with the realities of modern life in Iran. This year, the Valdivia Film Festival has a retrospective which brings some of his most acclaimed films to the tail end of the world for the very first time.

On the last day of the festival (and here we are obviously jumping ahead in time), Panihi presented his film The Circle which deals with the harsh realities that Iranian women have to face in post-revolution Iran. Here, urban Iranian women are depicted as defeated souls, lost in a maze of indifference, in a Tehran which brutally ostracizes and marginalizes women ("you can't go anywhere without a man"). The film takes turns following three loosely related female characters through the streets of Tehran. The first two women have been granted temporary release from prison and have no intention of returning, while a third women, whose story is casually taken up by the film towards the end, has escaped outright from prison and is desperately seeking arrangements for an illegal abortion. They frantically try to achieve their objectives, the first two wish to flee to a far away place and the pregnant woman seeks the help of old friends, but they fail to gain ground in an extremely closed society. There are many alludes to the question of freedom in Iran as well as to male domination, consequently, the film was banned there.

Comparing the treatment of women in the two films, we see immediately that there is nothing beautiful or worthwhile about the Iranian women in The Circle other than their obvious courage. One gets the impression that most of the time invested went into portraying Tehran as this terrible place full of danger and indifference at every corner, while almost no attention was dedicated to actually developing the female parts, characters who will no doubt be seen by western audiences as representing Iranian women in general. For the most part, they come across as one-dimensional and shallow. One never really feels a sense of injustice because the women never reveal their true humanity in the film. It sometimes feels as if Panihi, by forgetting to give these women personalities, is just as guilty of repressing them as the society he is trying to critique.

Wednesday, September 06, 2006

Festival de Valdivia 2006 PART II

Although the festival officially began on Friday night with the official inauguration and a couple of international films, the organizers ran out of tickets for these shows before we got our act together to find the place where they were actually giving them out. And so for us, really, the festival began on Saturday afternoon at the delightful Austral University campus (complete with botanical gardens) with two fine documentary efforts from Latin America.

Our first day of film-going went off quite smoothly, beginning in Argentina with a hard look at how the print media can distort political events with significant ease, and finishing up in Spain with an excellent character-driven film which attempts to show whether decent human beings can emerge from a highly competitive and psychological corporate selection process. In all, our Saturday movie-going session lasted about nine hours and was full of interesting surprises including a wonderfully delightful Chilean film directed by Rodrigo Sepulveda with a wonderful performance by Chilean actor Jaime Vadell.

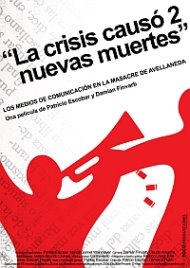

La Crisis Causo 2 Nuevas Muertes (The Crisis Caused Two New Deaths) was the June 27, 2002 Clarin newspaper headline which referred to the outcome of a violent barricade confrontation in Buenos Aires between Piqueteros and the police the day before. Two young activists, Maximiliano Kosteki and Dario Santillan, were murdered by the Argentinean police on that day but the newspaper Clarin, despite having possession of the incriminating photographs (and selectively publishing the ones that were ambiguous), distorted the events by claiming they did not have any information on who killed the piqueteros. The mainstream media followed Clarin's lead and distorted the events even further suggesting that a rival piquetero group was responsible. The film is a well- documented call for justice in the media, which is an important struggle in Latin American social movements. It is very common for the media in Latin America to play an active role in political confrontations, usually taking the side of law, order and stability and often blurring the repressive methods which are used to control popular opposition to neoliberal government policies. Very interesting. The film could have used a more concise "montaje" and a better narrative device; at times the information is overwhelming and the documentary tends to hit us over the head with its central thesis. A few technical flaws, especially in sound, but overall a great documentary and a good window into what has taken place recently on the other side of the Andes.

La Crisis Causo 2 Nuevas Muertes (The Crisis Caused Two New Deaths) was the June 27, 2002 Clarin newspaper headline which referred to the outcome of a violent barricade confrontation in Buenos Aires between Piqueteros and the police the day before. Two young activists, Maximiliano Kosteki and Dario Santillan, were murdered by the Argentinean police on that day but the newspaper Clarin, despite having possession of the incriminating photographs (and selectively publishing the ones that were ambiguous), distorted the events by claiming they did not have any information on who killed the piqueteros. The mainstream media followed Clarin's lead and distorted the events even further suggesting that a rival piquetero group was responsible. The film is a well- documented call for justice in the media, which is an important struggle in Latin American social movements. It is very common for the media in Latin America to play an active role in political confrontations, usually taking the side of law, order and stability and often blurring the repressive methods which are used to control popular opposition to neoliberal government policies. Very interesting. The film could have used a more concise "montaje" and a better narrative device; at times the information is overwhelming and the documentary tends to hit us over the head with its central thesis. A few technical flaws, especially in sound, but overall a great documentary and a good window into what has taken place recently on the other side of the Andes.

The great thing about documentaries is that they take you places you've never been before even if you've been there before. This is the central idea of the Venezuelan documentary, Macadam, directed by Andres Agusti. This film shows us a harsh Venezuela through the eyes of a highway. In a car or on a bus, the highway is a vessel that takes you past a thousand stories and realities you will never see or hear. These stories, nevertheless, exist on the ground and on the side of a road where the fierce sound of cargo trucks and microbuses passing by at excessive speeds interrupts an otherwise tranquil landscape of human existence. This filmmaker brings us close to those whose faces we see blurred as we speed by indifferently on our way through. And so even though the highway which dissects a Latin American country is a place most of us have experienced, we nevertheless learn something new about the lives those faces represent. The lack of narration and the lack of momentum might bother some people, but I think the vehicle of the film, this sort of slow introduction to each of the characters and the obsessive attention to detail interrupted abruptly by a passing bus whose driver is blasting cumbia, reflects effectively this harsh contrast between the fast-moving economic highway (flanked by the ubiquitous oil pipeline) and the slow passage of time lived by real people on the ground.

The second half of the day was reserved for fiction. The Chilean film Padre Nuestro was a delightful surprise. It is the story of a dying man whose dying wish is to reunite his estranged family for one last group photo in Quinteros, a beach community in central Chile, but not before spending a night out on the town in Valparaiso with his younger son who helps him escape from the hospital where his prognostic is bleak. He is a man who has lost everything that is important to him, his wife and his three children, and although he doesn't regret anything he has done (to the disdain of his daughter, played by Amparo Noguera), he recognizes that the only thing that matters is his family, whom he loves despite his fatherly limitations.

The second half of the day was reserved for fiction. The Chilean film Padre Nuestro was a delightful surprise. It is the story of a dying man whose dying wish is to reunite his estranged family for one last group photo in Quinteros, a beach community in central Chile, but not before spending a night out on the town in Valparaiso with his younger son who helps him escape from the hospital where his prognostic is bleak. He is a man who has lost everything that is important to him, his wife and his three children, and although he doesn't regret anything he has done (to the disdain of his daughter, played by Amparo Noguera), he recognizes that the only thing that matters is his family, whom he loves despite his fatherly limitations.

Our first day culminated with an exceptional film called El Metodo, a Spanish film directed by the Argentinian Marcelo Pineyro. This film takes us into the dark world of the corporate selection process. The story unfolds almost entirely in a corporate boardroom where a handful of candidates for the position are forced to participate in a highly evolved psychological selection game breaking all the rules of decency and mutual respect in the process. As a mass anti-globalization protest goes on below in the streets of Madrid, in the high rises we find out just how ruthless people can become in order to succeed in the highly competitive corporate world. The film's script is really incredible, as are all of the performances. Although we only share a few hours with the characters, the fluid and cutting edge dialogue is very entertaining and revealing.

Our first day culminated with an exceptional film called El Metodo, a Spanish film directed by the Argentinian Marcelo Pineyro. This film takes us into the dark world of the corporate selection process. The story unfolds almost entirely in a corporate boardroom where a handful of candidates for the position are forced to participate in a highly evolved psychological selection game breaking all the rules of decency and mutual respect in the process. As a mass anti-globalization protest goes on below in the streets of Madrid, in the high rises we find out just how ruthless people can become in order to succeed in the highly competitive corporate world. The film's script is really incredible, as are all of the performances. Although we only share a few hours with the characters, the fluid and cutting edge dialogue is very entertaining and revealing.

Our first day of film-going went off quite smoothly, beginning in Argentina with a hard look at how the print media can distort political events with significant ease, and finishing up in Spain with an excellent character-driven film which attempts to show whether decent human beings can emerge from a highly competitive and psychological corporate selection process. In all, our Saturday movie-going session lasted about nine hours and was full of interesting surprises including a wonderfully delightful Chilean film directed by Rodrigo Sepulveda with a wonderful performance by Chilean actor Jaime Vadell.

La Crisis Causo 2 Nuevas Muertes (The Crisis Caused Two New Deaths) was the June 27, 2002 Clarin newspaper headline which referred to the outcome of a violent barricade confrontation in Buenos Aires between Piqueteros and the police the day before. Two young activists, Maximiliano Kosteki and Dario Santillan, were murdered by the Argentinean police on that day but the newspaper Clarin, despite having possession of the incriminating photographs (and selectively publishing the ones that were ambiguous), distorted the events by claiming they did not have any information on who killed the piqueteros. The mainstream media followed Clarin's lead and distorted the events even further suggesting that a rival piquetero group was responsible. The film is a well- documented call for justice in the media, which is an important struggle in Latin American social movements. It is very common for the media in Latin America to play an active role in political confrontations, usually taking the side of law, order and stability and often blurring the repressive methods which are used to control popular opposition to neoliberal government policies. Very interesting. The film could have used a more concise "montaje" and a better narrative device; at times the information is overwhelming and the documentary tends to hit us over the head with its central thesis. A few technical flaws, especially in sound, but overall a great documentary and a good window into what has taken place recently on the other side of the Andes.

La Crisis Causo 2 Nuevas Muertes (The Crisis Caused Two New Deaths) was the June 27, 2002 Clarin newspaper headline which referred to the outcome of a violent barricade confrontation in Buenos Aires between Piqueteros and the police the day before. Two young activists, Maximiliano Kosteki and Dario Santillan, were murdered by the Argentinean police on that day but the newspaper Clarin, despite having possession of the incriminating photographs (and selectively publishing the ones that were ambiguous), distorted the events by claiming they did not have any information on who killed the piqueteros. The mainstream media followed Clarin's lead and distorted the events even further suggesting that a rival piquetero group was responsible. The film is a well- documented call for justice in the media, which is an important struggle in Latin American social movements. It is very common for the media in Latin America to play an active role in political confrontations, usually taking the side of law, order and stability and often blurring the repressive methods which are used to control popular opposition to neoliberal government policies. Very interesting. The film could have used a more concise "montaje" and a better narrative device; at times the information is overwhelming and the documentary tends to hit us over the head with its central thesis. A few technical flaws, especially in sound, but overall a great documentary and a good window into what has taken place recently on the other side of the Andes.The great thing about documentaries is that they take you places you've never been before even if you've been there before. This is the central idea of the Venezuelan documentary, Macadam, directed by Andres Agusti. This film shows us a harsh Venezuela through the eyes of a highway. In a car or on a bus, the highway is a vessel that takes you past a thousand stories and realities you will never see or hear. These stories, nevertheless, exist on the ground and on the side of a road where the fierce sound of cargo trucks and microbuses passing by at excessive speeds interrupts an otherwise tranquil landscape of human existence. This filmmaker brings us close to those whose faces we see blurred as we speed by indifferently on our way through. And so even though the highway which dissects a Latin American country is a place most of us have experienced, we nevertheless learn something new about the lives those faces represent. The lack of narration and the lack of momentum might bother some people, but I think the vehicle of the film, this sort of slow introduction to each of the characters and the obsessive attention to detail interrupted abruptly by a passing bus whose driver is blasting cumbia, reflects effectively this harsh contrast between the fast-moving economic highway (flanked by the ubiquitous oil pipeline) and the slow passage of time lived by real people on the ground.

The second half of the day was reserved for fiction. The Chilean film Padre Nuestro was a delightful surprise. It is the story of a dying man whose dying wish is to reunite his estranged family for one last group photo in Quinteros, a beach community in central Chile, but not before spending a night out on the town in Valparaiso with his younger son who helps him escape from the hospital where his prognostic is bleak. He is a man who has lost everything that is important to him, his wife and his three children, and although he doesn't regret anything he has done (to the disdain of his daughter, played by Amparo Noguera), he recognizes that the only thing that matters is his family, whom he loves despite his fatherly limitations.

The second half of the day was reserved for fiction. The Chilean film Padre Nuestro was a delightful surprise. It is the story of a dying man whose dying wish is to reunite his estranged family for one last group photo in Quinteros, a beach community in central Chile, but not before spending a night out on the town in Valparaiso with his younger son who helps him escape from the hospital where his prognostic is bleak. He is a man who has lost everything that is important to him, his wife and his three children, and although he doesn't regret anything he has done (to the disdain of his daughter, played by Amparo Noguera), he recognizes that the only thing that matters is his family, whom he loves despite his fatherly limitations. Our first day culminated with an exceptional film called El Metodo, a Spanish film directed by the Argentinian Marcelo Pineyro. This film takes us into the dark world of the corporate selection process. The story unfolds almost entirely in a corporate boardroom where a handful of candidates for the position are forced to participate in a highly evolved psychological selection game breaking all the rules of decency and mutual respect in the process. As a mass anti-globalization protest goes on below in the streets of Madrid, in the high rises we find out just how ruthless people can become in order to succeed in the highly competitive corporate world. The film's script is really incredible, as are all of the performances. Although we only share a few hours with the characters, the fluid and cutting edge dialogue is very entertaining and revealing.

Our first day culminated with an exceptional film called El Metodo, a Spanish film directed by the Argentinian Marcelo Pineyro. This film takes us into the dark world of the corporate selection process. The story unfolds almost entirely in a corporate boardroom where a handful of candidates for the position are forced to participate in a highly evolved psychological selection game breaking all the rules of decency and mutual respect in the process. As a mass anti-globalization protest goes on below in the streets of Madrid, in the high rises we find out just how ruthless people can become in order to succeed in the highly competitive corporate world. The film's script is really incredible, as are all of the performances. Although we only share a few hours with the characters, the fluid and cutting edge dialogue is very entertaining and revealing.

Tuesday, September 05, 2006

Festival de Valdivia 2006: PART I

The clasico Tur-Bus service is the crappiest spike in the Tur-Bus service trident. The other two are the "ejecutivo", which you can bet has not one single "ejecutivo" on it, and "cama", which is essentially a bus full of jerk-offs lying horizontally. "Clasico", by the way, is code for "there's no way my legs are fitting in there!" Since our bus was a night bus, complete with blankets contaminated with chicken pox and pillows designed for Lilliput, our bus careened out of the alameda bus terminal with a fifty-fifty chance of crashing head-on into something large and immobile.

The clasico Tur-Bus service is the crappiest spike in the Tur-Bus service trident. The other two are the "ejecutivo", which you can bet has not one single "ejecutivo" on it, and "cama", which is essentially a bus full of jerk-offs lying horizontally. "Clasico", by the way, is code for "there's no way my legs are fitting in there!" Since our bus was a night bus, complete with blankets contaminated with chicken pox and pillows designed for Lilliput, our bus careened out of the alameda bus terminal with a fifty-fifty chance of crashing head-on into something large and immobile.The "auxiliar" made his way down the aisle in typical neanderthal fashion, writing down passenger names for post-crash identification purposes, and I suddenly realized that I was hungry for bus food. Traveling around Latin America by bus will never be complete without bus food. It doesn't really matter what time of day it is, it is scientifically proven that buses in Latin America, even Chile, trigger immediate hunger. If for any reason you've been taking it easy on the cookies, chips and colored drinks, a night bus ride is your chance to catch up on lost moments of junk food sucking. Standard bus food consists of "Fracs", or local equivalent, a tube full of generic "pringles", a cheese-bread thing, and for dessert, Unimarc manjar balls with cocunut springles. Fantastic! The rest of the bus ride consisted of brief intervals of sleep and praying.

First Impressions of Valdivia

Arriving in Valdivia early Friday morning was, for me, somewhat of a let-down, at least visually. Except for the happy meeting of rivers, a few mediocre forts (that charge you for the view they afford!), and the overall country feel, Valdivia is just another "could be anywhere" town in southern Chile. Everybody had told me that Valdivia was "something really special", and I'm sure they know what they're talking about, and I'm sure they're right (I've only been here for one day, after all), however, I can't help but feel the way I do, "let-down". Maybe the "classic" Tur-Bus night service had something to do with it, or the food I ate which was making me physically nauseas, the point is Valdivia, at least at first glance, left a lot to be desired.

No Spanish

Ironically, part of the problem is that this end of Chile was never really conquered by the Spanish (people here speak valdivian) and so you see almost no Spanish architecture, which is so visually rewarding. There are no "fuck all" cathedrals with their pompous and exaggerated details, no sign of the visual wealth (at least) left behind in places like Potosi or Sucre in Bolivia. I'm a spoiled traveler, I guess, and maybe it's a good thing the Mapuches were never really overrun by the Spanish, except that a few years later they were overrun by the Chilean state in a "process" much more abrupt and bloody in comparison. With the Spanish, at least you had this sort of missionesque "we're here to save you from yourself and please cover your testicles" type of discourse with the "natives". With the Chilean army, it was a much more modern, and hence cold, type of "extraction" which encouraged post pacification immigration and turned these parts into boring towns full of drunk Germans. En fin.

Not Santiago

Most of the praise for Valdivia, I suspect, is exaggerated by Santiaguinos because for them, any place that is not Santiago seems like a paradise, especially if there are a few rivers you can stare at without feeling nausea or air for your lungs. The other thing that disappointed me was the porfiado presence of commercial franchises that also contribute to the homogeneity of southern Chile. It's like the municipality tries to "improve" the city by making it look more like Santiago, complete with its "fuck all" shopping malls, instead of more like Valdivia. So when you're in town, you see the same mediocre chains of decadent commercial interests (which people, in any case, go nuts for), malls, jumbo supermarkets, McDonalds, Mass Pharmacies, Cineplexes, Electrodomestic department stores, Blockbusters. I guess they call this "progress", "integration", "modernity" or the latest catch word, but in Sucre, or other places in Bolivia, for example, you don't really see those sorts of things and you would never suggest that the answer to all their problems, of which there are plenty, is to bring in a La Polar or a Blockbuster.

Swans with Black Necks

The other thing which has marked Valdivia lately has been its leading role in the so-called "environmental wars" that have been "waged" in Chile, recently. Of course, the Pulp treatment plants have been present in the south for many years and contamination is not a new thing; the environmental "issue", however, is a relatively new phenomenon. Last year, the media exploded the issue of the black neck swans, who basically all died, quite dramatically, and on TV. Residuals from a pulp mill killed off the swan's primary source of nutrients. The media went ape shit and government representatives were forced to make a few speeches about the importance of the environment and on the importance of not killing swans. The plant closed itself down (which was bizarre on the one hand and clearly evidence of some sort of secret deal reached with the government on the other) and then opened again with promises to contaminate the coastline instead. A few complicated and scientific-sounding studies were released to the media and the whole country became confused as to the real causes of the deaths of the swans. Was it the lack of food, or was it a mass swan suicide promoted by too much food?

En fin, in the end, nothing was done and it became clear that the environment, while extremely noble and important, cannot jeopardize the nobler pursuit of supplying Asian countries with lots of pulp from our unrenewable forests in exchange for cheap washing machines, televisions, sandwich makers, and consumer debt. Nobody, by the way, brought up the issue of human contamination. Those types of effects are considered "long term", which in Chile, as in most countries, is a concept that is rarely taken seriously.

Drunk Germans

There's also beer here in Valdivia! Kunstmann beer is a German beer made in Valdivia (about 10 km from the center of Valdivia) and in their merchandizing material you can make out the glorious X Chilean Volcano and the beautiful Lakes and all that. We were assured on the tour that the company is one hundred percent Chilean, providing jobs for as many as 32 Valdivians (!) and generously supporting the local economy and municipality (US$ 6,000 a year!). In the museum, along with the typical rudimentary machines used to grind stuff, you can also see the long string of bearded Germans who've owned the company over the years as well as an assortment of photographs taken during the Valdivian version of a beer fest (complete with the queen of rivers looking quite German). There's a substantial German influence in this region and, call me crazy, I get the impression that the people in the oversized supermarket stare at me with German eyes!

Film Festival

But the real reason our team of documentary film students from Santiago is here is to take part in the 13th International Film Festival of Valdivia! I have no idea how this festival began and why it began in Valdivia (must find out!) but it seems to be a big deal in Chile. The Chilean film industry is almost non-existent but what little there is seems to conjugate here at the end of August to enjoy and critique the latest Chilean features, shorts, and documentaries alongside student offerings, animation, and a few international films that are incorporated into the main competitions and also as part of a series of special "homages" and "tributes" and all that payasada. This year, there is a strong focus on Argentinian films. Included in the program is a historical and cultural forum lead by Luis Bocaz, analyzing the cultural impact these political films have had on Argentinian society. The majority of these films tackle the often violent political developments in Argentina during the second half of the twentieth century.

Aside from this cycle of political film analysis, there are a variety of films that interest me, or filmes que me tincan. There are documentaries that tackle interesting and complex social and economic realities, especially in Argentina, there is an attempt to define the Mapuche cosmovision, there is a much-awaited and unreleased Chilean comedy, there is the latest Almodovar film, and there's a groundbreaking Bolivian film! Topping the list of films that are in competition for best feature-length is the worst and most pretentious Chilean film in history, "Fuga", a film whose executive producer is also part of this year's jury for the same category. Hello? So far, our pre-festival experience has given us the impression that this event is as big of a let-down as Valdivia, and this "controversy" forms part of that first impression. It's just a first impression though.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)